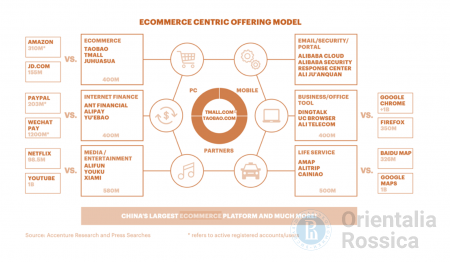

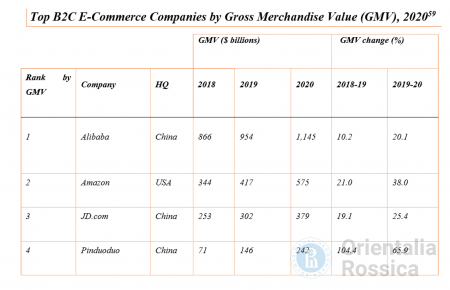

Alibaba |

- the largest Chinese and the world’s largest B2B e-commerce marketplace;

|

- covers 80% of online sales in China;

|

- operates in 200 countries;

|

- also operates other huge e-commerce sites such as AliExpress, TMall and Taobao.

|

AliExpress |

- Alibaba-owned marketplace that targets buyers outside China;

|

- offers international shoppers goods at factory prices without a minimum order size;

|

- has users from over 220 countries;

|

- has a global English site and operates in 15 other languages.

|

Flipkart |

- India’s largest marketplace with over 10 million customers and 100,000 suppliers

|

HipVan |

- Singapore-based e-commerce platform

|

- offers goods from design studios and independent designers

|

- its aim is to fight with low quality goods from China

|

JD.com |

- the second-largest Chinese B2C marketplace with over 300 million users.

|

- Kaola, Tmall, Taobao are also huge Chinese marketplaces. Taobao is listed as the ninth most visited website in the world.

|

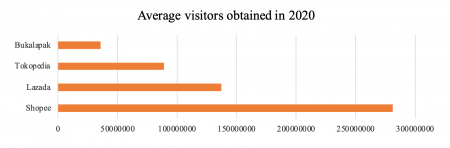

Lazada |

- is also called “the Asian Amazon”

|

- operates in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam

|

Qoo10 |

- Singapore-based marketplace operating in China, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Hong Kong

|

- accounts for more than a third (32.6%) of Singapore’s ecommerce market

|

Rakuten |

- Japanese marketplace selling over 18 million products

|

- has over 105 million members in Japan, it has the largest market share in the country – around 80% of Japan’s population buy from their site

|

Shopee |

- one of the leading mobile e-commerce platforms in Southeast Asia

|

- operates in Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Taiwan, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines

|

Snapdeal |

- India-based marketplace with over 40 million users, 300,000 sellers and 35 million products

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий